As local economies continue to recover from the pandemic downturn, policymakers are focused on how best to use public policy tools to support resilient and equitable economies. Like many cities, Oakland is examining how its business tax structure aligns with the city’s goals and needs. The City Council is considering a proposal to restructure the city’s gross receipts tax to create tiers based on the amount of gross receipts, as well as a new administrative headquarters payroll-based tax. The current proposal being put forward by Council Members Bas and Fife would raise an estimated additional $40 million for the city’s general purpose fund, and would go before voters in November 2022.

When policymakers propose to increase taxes, they are commonly met with claims that such changes will discourage businesses from locating or expanding and may even cause businesses to move jobs to other jurisdictions. In truth, there is limited research evidence in support of the assertion that local taxes play a significant role in business location decisions. Furthermore, the tools used to create estimates of the job impacts of tax changes are much less reliable than they are often presented to be. As part of our work assessing the impact of public policies on the labor market, we reviewed the impact analysis performed for the council by Blue Sky (included in the October 2021 Task Force report) and subsequent estimates that the current proposal will cause the loss of between 1,600 and 3,400 jobs. We also explain the value that increased revenue would have for Oakland businesses, including improved services and staff to address the issues that businesses have identified as important needs.

In adopting Resolution 88227 to create the Blue Ribbon Equitable Business Tax Task Force, the City Council articulated these goals for Oakland’s economy: “revenue enhancement, reduction of race and equity disparities, tax code modernization, equitable economic development, and living wage job creation.” A progressive business tax structure is one element of city policy that can support these goals, by improving public services and revenue adequacy while allocating responsibility for those goals according to business size. Oakland’s small businesses in particular—which generate economic activity that stays local and supports Oakland’s residents of color—could benefit from both a reduced tax burden and additional city funding to provide general business support. A progressive business tax equitably shifts responsibility to the city’s largest businesses to benefit Oakland’s long-term economic health and is in alignment with the approaches being taken by similar jurisdictions.

Structure of Oakland’s gross receipts tax

In 2019-20, about 60% of the city’s business license tax revenue came from the GRT; the remaining 40% came from commercial and residential rental income tax (Oakland budget website). Business license tax revenue was $98.0 million in FY2019-20; despite the pandemic’s impact on many businesses, business license tax revenue rose to $104.3 million in FY2020-21, up 6.6%. This represents about 12% of the city’s general fund revenues.

Oakland’s current GRT sets a minimum payment of $60 and a flat rate per $1,000 of gross receipts (or payroll, for some businesses); those rates vary by sector but not by business size. In 2020, members of the Oakland City Council put forward a proposal to restructure the GRT to base the rate on the volume of gross receipts, thus providing relief to small businesses, shifting the burden to larger businesses, and raising significant additional general revenue funds for public services. The council then created the Blue Ribbon Equitable Business Tax Task Force which published a report in October 2021 analyzing the potential impacts of the tax and proposing an alternative formulation.

The report presented an alternative proposal with slightly different rates and an additional new administrative headquarters tax for firms with more than 1,000 employees in the U.S. and $1 billion in revenue ($15 per $1,000 of Oakland-based payroll). The current proposals set marginal rates per $1,000 based on brackets of gross receipts; those rates range from $0.45 (for groceries under $1 million) to $10.80 (for business/professional services with over $100 million in gross receipts). In March 2022, Council members Bas and Fife put forth a proposal that adopts most of the Task Force rates, adds a tier of $100 million and above for several sectors, and includes the Task Force’s administrative headquarters tax. The proposal leaves untouched tax rates for Residential Rental, Commercial Rental, and Cannabis sectors; Trucking & Transportation and Taxicabs, Ambulances & Limousines would fall under a proposal made by Council Member Kalb in 2020. According to data provided to City Council, the affect sectors accounted for 49% of total gross receipts revenue in FY2019-20. In our analysis, we focus on the current proposal put forward by City Council members Bas and Fife.

It’s important to remember that Oakland businesses pay numerous taxes and fees in addition to the city’s gross receipts tax, and most businesses will be able to deduct gross receipts tax payments when calculating net income for state and federal corporate income tax, so the percentage increase in GRT equates to a much smaller increase in overall tax responsibility. The total amount of corporate tax collected by the state exceeds that collected by local governments, so we can presume that it constitutes less than half the total taxes paid by Oakland’s largest businesses, particularly those impacted by the largest GRT increases.

Progressive tax structures are good economic policy

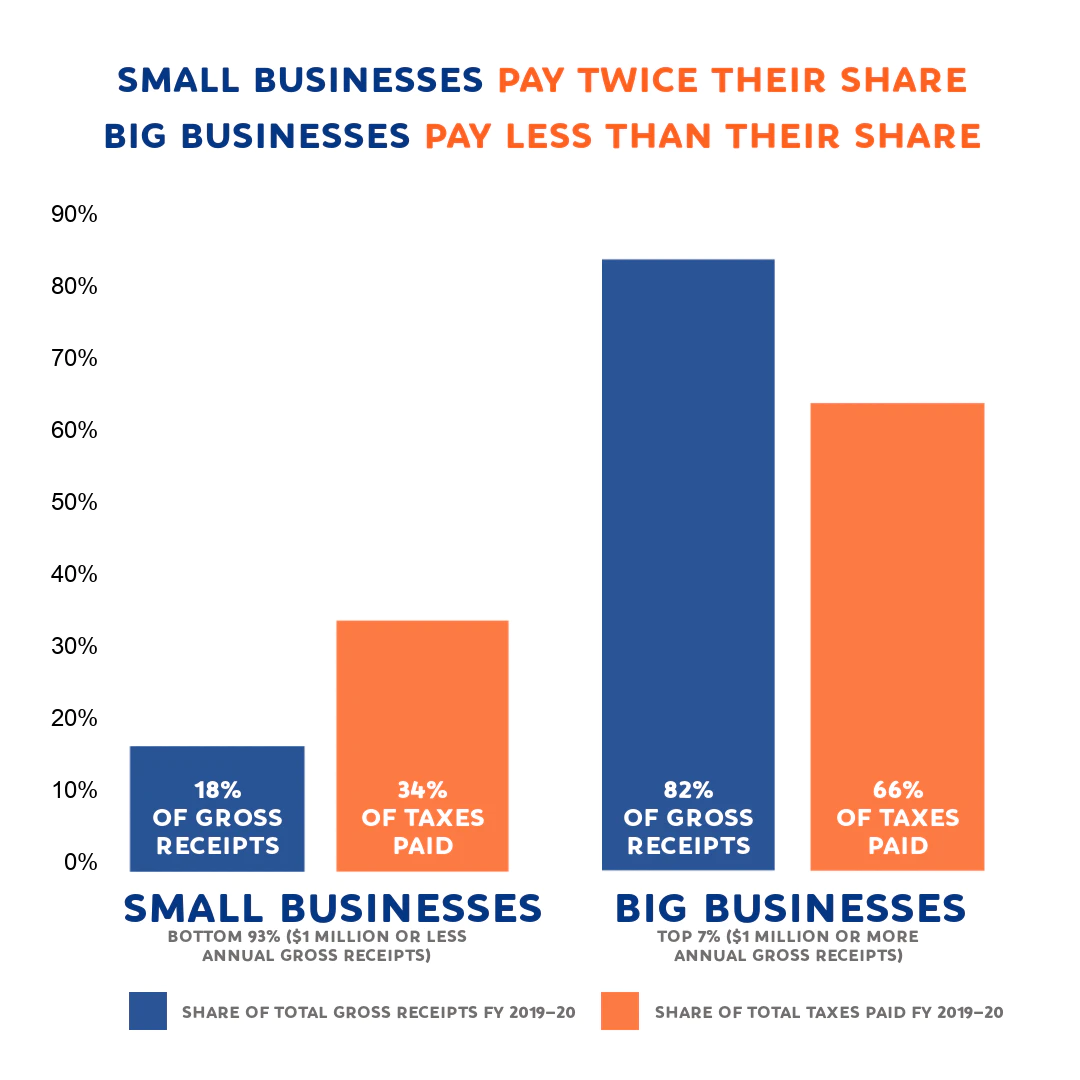

A progressive GRT would reduce the tax burden on small businesses and generate significantly more tax revenue for public investments that help grow and sustain Oakland’s economy, and to meet the goals set by the Council in creating the Task Force. The Bas-Fife proposal (like the other iterations) would levy additional revenues primarily from the city’s largest businesses, and would significantly redistribute the tax burden to better reflect businesses’ ability to contribute. For example, under the current tax structure, Oakland’s small businesses with $1 million or less in gross receipts account for 18% of payroll and gross receipts but account for 34% of business tax revenue.

A good tax structure needs to meet several criteria: be equitable and transparent, part of a stable revenue mix that can provide cyclical stability, evenly enforced, and adequate for funding needed services. Tax responsibility by sector and business size would reflect businesses’ ability to pay, the structure of Oakland’s economy, and the economic development strategy of the city, including its position within the regional economy. Oakland’s business taxes lag far behind San Francisco, the closest large city in the regional labor market. The order of magnitude of that gap is enormous for some industries, while San Francisco (along with most other cities) provides a more favorable structure for small businesses and collects significantly more revenue. Businesses that have moved from San Francisco to Oakland benefit from closer proximity to the Bay Area workforce (which has been migrating to Oakland and more exurban Bay Area cities for several years, in response to astronomical housing costs and limited construction in San Francisco), lower residential and commercial real estate prices, and more diverse transportation infrastructure. An equitable tax structure will make Oakland a more favorable place to start a new business, in line with San Francisco and Richmond. The current flat-rate tax structure also means that the city is not adequately tapping into its tax base and calling upon its largest companies to invest in the city to sustain long-term economic growth. Progressively structured revenue programs to fund public services is a hallmark of good economic policy.

The Bas-Fife proposal (Table 1) effectively raises about $40 million in additional revenue by shifting tax responsibility to the largest businesses in Oakland, using marginal tax rates that increase up to the highest bracket of $100 million or above (a category that includes 21 firms accounting for 15% of gross receipts in FY2019-20) (Bas-Fife March 17 memo). The vast majority of Oakland businesses will see no tax increase under this proposal, and many of those affected will see very small increases.

All told, a small percentage of Oakland businesses will face any significant increase in GRT under this proposal (see Table 2). Of the 24,979 businesses in affected sectors, just over 1,200 firms face an increase of more than 25% (amounting to less than a 0.1 percentage point increase).

- City staff estimate that only 10 of the 94 administrative headquarters currently licensed in Oakland would pay the proposed alternative flat rate per payroll tax, a total of an estimated $7.7 million in 2023-24, with nearly 80% of that paid for by just two taxpayers.

- Oakland’s top 10 business accounts will pay $21.9 million in taxes under the Bas-Fife proposal; that constitutes 24.7% of the affected sectors’ business taxes (up from 11.3% in FY2019-20). (These accounts are not the same as the city’s top ten largest employers, which are primarily public and nonprofit entities, employing just over a quarter of Oakland workers.)

- The 24 largest firms (those with more than $100 million in gross receipts or Oakland payroll)—will pay an additional $20 million under the Task Force proposal, about half of the total increase of $40 million.

The progressive tax structure is also important for the City of Oakland’s commitment to expanding economic justice—entrepreneurs of color own businesses that grew 10 times faster than U.S. small businesses overall from 2007 to 2017. Although the number of firms has grown quickly, the average gross receipts for minority-owned firms has dropped. Reducing the tax burden will support small businesses that are started by people of color, which is advantageous for Oakland’s economic climate and attracting diverse talent to Oakland. Oakland’s small businesses were disproportionately affected by the pandemic recession; relying on larger businesses for the tax base will help stabilize Oakland’s revenues. 5,578 businesses with owners or CEOs from an underrepresented racial/ethnic group would receive a tax cut, compared to 4,420 white-owned businesses.

Small businesses generate economic growth that primarily stays local. Implementing tax policy that supports small business growth is also important for the broader local economy—small businesses create 2/3 of net new jobs and account for 44% of U.S. economic activity. There is strong community support for small businesses in Oakland—in addition to creating jobs, small businesses build community identity and encourage entrepreneurs to innovate in Oakland.

In addition to reducing the taxes paid by small businesses, the proposed uses of the increased revenue will benefit small businesses in Oakland. The recommendations include support of small business loan initiatives and shared city resources for small businesses, such as hiring additional City staff and funding the City’s Business Improvement Districts. Staffing up capacity to support businesses at the city level will reduce the administrative burden for small businesses who are navigating the administrative red tape. Small businesses have limited resources and staff capacity to navigate bureaucracy, so this additional revenue will make the City more responsive to small business needs.

It is also worth noting that the share of state and local government tax revenue accounted for by corporate taxes has shrunk over the past two decades, and has not been made up for by other revenue sources. Large national firms in particular have been experiencing lower effective tax rates despite growing profitability—corporate profits grew 25%in 2021, after a 5% decline in 2020.

Oakland economic forecast and recovery

The Labor Center has done significant research since March 2020 on the impacts of the pandemic on both public sector budgets and workers and employment in California. Compared to the nation as a whole, California lost a greater share of jobs during the early months of the pandemic and has recovered them more slowly (author’s analysis of BLS CES data). As of November 2021, the state had recovered 75% of those jobs across all industries. Several industries—transportation/warehousing/utilities, construction, administrative services, and retail, have grown faster than the economy as a whole (Table 3). Government employment, however, has lagged well behind the private sector, recovering only 57.5% of jobs lost, despite significant infusions of one-time state and federal funding. Local government has lagged behind all other employment sectors, still down 6.2% from February 2020 in California, compared to 1.5% for all nonfarm employment. Research on the long and mixed recovery after the Great Recession suggests that this stagnation of state and local government employment is bad for the long-term economic outlook.

The Bay Area’s economic recovery has lagged slightly behind the state on some measures (Table 3), but unemployment continues fall, down to 4.3% in Alameda County in February 2022, down from a high of 14.6 in April 2020 and below California’s rate. Unemployment rates have diverged widely, however, by race/ethnicity and gender; the unemployment rate for Black Californians is almost twice as high as for whites in February 2022.

Job loss and recovery have varied widely by industry, more so than in a “typical” recession. The two hardest-hit industries by absolute job loss are Leisure & hospitality and Government, accounting for over 30,000 lost jobs from February 2020 to February 2022. Other sectors have bounced back and grown significantly over the past year: transportation/warehousing/utilities by 14 percent since February 2020, and manufacturing by 7 percent.

There is continued uncertainty about how downtown areas and commercial districts will be affected by continued hybrid and remote working arrangements, particularly as housing costs continue to escalate in most large U.S. cities. It is likely that there will be some restructuring of commercial location patterns, particularly among white-collar service jobs that can be performed remotely. But for employers that need / want their workers to resume in-person office work, the core economic development drivers of urban amenities, public safety, quality of public services, will continue to be important location factors. Shifts in patterns of consumption and business travel have hurt the fiscal health of cities that rely heavily on sales taxes and transient occupancy taxes for revenues, such as San Francisco. Diversifying local revenue sources is an important economic development strategy; business license taxes based on volume of gross receipts will mean that Oakland benefits when its largest businesses do well, as most of them did over the past two years. California’s progressive tax structure permitted the state to maintain vital services and protect the state’s economic stability as its wealthiest taxpayers prospered during the pandemic.

Oakland’s 2018-20 Economic Development Strategy established three objectives: increasing economic productivity, improving economic security, and reducing racial wealth disparities. The city’s Economic Recovery Plan emphasizes closing race and gender disparities and helping businesses owned by people of color and women, as well as lower-wage workers, recover from the pandemic. Efforts include a business attraction program for core businesses, improving support for businesses to navigate the permit process, and supporting innovation in local manufacturing.

Oakland is attractive to large regional and national employers because of its skilled labor market, public infrastructure, agglomeration economies (particularly specific clusters in healthcare), and environment for innovation. The personal and business services that support core industries are drawn to important industry clusters and residential and commercial density, and by the spending power of the city’s residents and workers. Oakland’s economic success is not driven by low costs in labor or real estate but by the strengths of its labor market, institutional support for innovation, and proximity to local and regional consumer markets. These strengths also include:

- Robust labor supply: high education levels, diverse skills, and an attractive location for potential employees.

- Agglomeration economies in healthcare and other core industry clusters.

- Proximity to major education and research institutions.

- Infrastructure that facilitates a strong transportation and logistics cluster, including highway, rail, and a major port.

In recent years, these strengths have enabled Oakland to compete successfully with San Francisco and Silicon Valley for headquarters, not on the basis of lower taxes but because workers have more opportunities for housing in Oakland and surrounding areas, and the flourishing of Oakland’s cultural scene makes it an attractive place to locate.

Oakland also faces challenges as it seeks to foster economic recovery and equity:

- Escalating housing costs and associated increases in homelessness

- Business, resident, and worker concerns about safety and cleanliness

- Sufficiency and stability of city revenues

- Income inequality and high unemployment for some groups of Oaklanders

These strengths and challenges affirm the importance of adequately funding public infrastructure and public services that are responsive to the identified needs of Oakland’s businesses and workers and the priorities of Oakland’s leaders.

How businesses respond to tax increases

Taxes are just one element of businesses’ decision-making about location or expansion, and they are not determinative. As Blue Sky presented to the Task Force in May 2021, there are many factors that drive business cost structures, including labor availability, occupancy costs, taxes, and inputs (e.g. supplies, raw materials, etc.). Businesses must also consider the accessibility to customers (which could be patients, consumers, or other businesses), and many factors that affect the day-to-day convenience of doing business (e.g., necessary infrastructure, regulatory support, safety), and the perceived desirability to employees (e.g., local amenities, public goods). Some of these apparently “intangible” items—safety, amenities—actually drive the cost of doing business.

The following elements have all been demonstrated to contribute to business decisions about location or expansion:

- Labor accessibility and quality

- Occupancy costs: commercial rentals, real estate costs, utilities, etc.

- Adequacy of public infrastructure

- Safety, cleanliness, accessibility for both employees and customers

- Urban and localization agglomeration economies (the economies of scale that come from being located close to similar companies, drawing on supplier pools and innovation networks, and in dense urban areas with diverse labor markets and advanced business services)

- Customer base (including business-to-business)

- Overall tax burden: state corporate taxes, property tax, business license tax

- Preferences of decision-makers

There is very mixed evidence for the importance of any of these individual factors. In economic development research, it has always been difficult to isolate the causal impact of any one factor, particularly as in an environment of lobbying for either specific incentives or broad tax reductions, businesses have a disincentive to reveal their true interests. (In fact, businesses (and their advocacy organizations) have an incentive to overstate the importance of tax policy on their decision-making, which several researchers have noted). Some businesses are more mobile than others, as the costs of moving vary significantly by industry and size. Costs of moving include not just the costs of relocating and replicating fixed investments such as plants or hospitals, but the impact on productivity of moving further away from key inputs, and the benefits of access to labor pools with specific skills or to a large, dense labor pool with many skills. Educational opportunities, a strong labor market, and quality of life play a large role in places’ abilities to attract skilled workers.

Estimating the job impacts of tax changes

For many of the reasons above, efforts to quantify estimated job impacts of tax changes should be accompanied with many caveats, but are often presented as something more akin to a science. Because Oakland’s proposed GRT restructuring affects different sectors and business sizes differently, estimating the degree of tax impact on groups of jobs is very complicated. Different sectors and even businesses within the same sector can face very different cost structures and incentives. Job impact analysis such as that performed by Blue Sky typically uses proprietary tools—such as REMI—that are based on built-in assumptions about the relationship between taxation and employment. These tools do not have a strong track record for post-evaluation, meaning that the models are not regularly adjusted.

For the Bas-Fife proposal, Blue Sky estimates that between 1,600 and 3,400 jobs (about 1% of the city’s private sector employment) might be lost if businesses subject to increased GRT rates move jobs out of Oakland or reduce hiring in response to the tax changes. The range in estimates for revenue and job impacts are based on three scenarios:

- Static elasticity scenario: estimates of increased revenues with no business response (and therefore no employment change)

- Constant elasticity scenario: elasticity of -0.2: this elasticity is based on Blue Sky’s summary of the literature, from which they draw the conclusion that a 10% change in total tax burden leads to a 2% change in economic activity. It’s not clear how the total burden would be calculated given the significant share of overall business taxes taken up by state corporate taxes and property taxes. For the vast majority of businesses, the GRT increase alone would be less than 10%, so the total tax burden change is significantly less than that (Blue Sky notes this in their own report on the possible elimination of the GRT in Los Angeles, published in 2012, citing Bartik’s research).

- Variable elasticity scenario: range in elasticity of -0.1 to -0.6 depending on the scale of the tax increase (so a larger percentage increase in taxes would produce a larger change in economic activity).

There are several challenges to estimating job impacts of a tax change like the Oakland proposal:

- The first challenge in estimating employment impacts is that we don’t have specific data on the number of people employed in the affected sectors or for taxpayers by size bracket. The city only has data on the number of taxpayers by sector and amount of gross receipts. We obtained the table constructed using city data showing the number of employers by industry and gross receipts bracket (although some of the gross receipts amounts were not tied to specific tax brackets because of confidentiality issues). In order to construct estimates of the number of people employed in affected sectors, we replicated Blue Sky’s approach. We obtained Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) data for the San Francisco MSA to estimate a relationship between gross receipts and employment in order to calculate an employment number from the city’s gross receipts data. These ratios, however, can vary a lot by company and company size, and the nature of the location (for example, different locations of the same company are categorized as the same industry but can have a very different set of occupations, such that the relationship between gross receipts and employment is not static even across locations owned by the same company).

- It’s difficult to estimate a percentage tax increase for the mix of affected firms that could be used to apply a model like Blue Sky uses, which relies on a correlation between tax increase and changes in economic output. The brackets are marginal tax brackets, meaning that the top bracket paid does not represent their effective gross receipts tax rate. And as mentioned above, GRT can be deducted from state and federal corporate income taxes. This makes an analysis of this tax impact much more complicated than, for example, an across-the-board rate increase (such as the implementation of a flat tax).

- Any impact analysis modeling the effect of tax increases would of course also need to include the increased employment and spending associated with the additional revenues; impact models such as REMI should have this built into their impact estimates, but those details have not been provided as part of this analysis.

- In the case of Oakland’s GRT, the small number of businesses affected, the wide variation in the degree of rate increase across sectors and sizes, and the variation in location drivers between sectors makes an across-the-board impact percentage difficult to evaluate.

- Predicting how businesses will respond to a relatively minor increase in taxes is exceedingly difficult. Many of the businesses most impacted have significant annual profits; these businesses have already chosen to locate in Oakland understanding that the costs (wages, real estate) come with accompanying benefits (skilled workers, agglomeration economies).

Using Blue Sky’s method of using SUSB data on the relationship of gross receipts to employment, we estimate that 51,451 jobs are in firms subject to any increase (Table 4); those increases could range from 0.01 percentage points to 0.92; 34,668 jobs fall under the brackets facing less than a 0.1 percentage point increase. These are not scientific estimates by any means, but give us a baseline for evaluating the magnitude of the change Blue Sky has projected. Blue Sky has estimated total job losses ranging from 1,600 to 3,400. If these were direct job losses, that would represent a 6-10% employment decline by affected firms, a significantly larger response to taxation than economic development research would suggest. Blue Sky has indicated in statements that its numbers include indirect and induced impacts of direct job loss, although that is not clear from their report. If we assume about a 1.4 multiplier (because we don’t know what direct job losses might occur), that would mean their estimates are based on about 1,150 to 2,400 in direct job losses (or more, if these are offset by the job increases created by additional revenues). That still represents a larger degree of impact than the research suggests is likely.

Extensive research shows that cost increases—such as minimum wage policies—do not produce the job reductions that conventional economic wisdom once commonly assumed would follow. Research has shown that businesses are able to pass those costs on to consumers or—particularly in the case of the large national businesses who will be most affected by the GRT increase—to investors.

Many impact analyses like this are presented with the caveat that economic impact analysis is not an exact science, but rather a guide to what might happen based on the relationships that businesses have with each other in an economy. Tools that were developed to be able to apply specified changes in business costs onto a regional economy may not be informative about how a small set of economic actors are likely to behave and how that will then impact a local economy. That’s not to say that a tax increase will never contribute to a company’s decision to leave or downsize its presence in Oakland, but any estimates of the net effect of these changes are by nature based on generalized assumptions with a significant margin of error. Estimates of economic impact of new projects (such as sports stadiums) do not have a very good track record and have fallen out of favor significantly since their initial development in the 1980s and 1990s. Some of this lies in the difficulty in assigning causal impacts in a complex economy in which economic cycles, national trends, market prices, and individual preferences are difficult to isolate from the event being studied. What we do know is that investing in Oakland’s strengths, and addressing its challenges, will require public investment by Oakland’s largest businesses.

Neighboring city taxes

Any effort to estimate the impact of a tax structure change should be considered in light of the tax structure of neighboring jurisdictions and trends in business tax policy; several large California and Bay Area cities have moved toward a progressive business in recent years. Two neighboring cities—San Francisco and Richmond—have implemented progressive gross receipts taxes.

The City and County of San Francisco adopted a progressive tax in 2012 that gradually replaced payroll taxes. Two additional taxes on gross receipts for commercial real estate businesses and large businesses were adopted in 2018; the full phase-in of current rates took effect just before and during the pandemic. The intent of San Francisco’s shift to a progressive GRT was to address inequities in the payroll tax, generate additional tax revenue, and spur job creation. Oakland’s business tax revenue per firm—particularly for the largest firms—is well behind San Francisco and other jurisdictions. San Francisco’s current administrative headquarters tax (for those meeting the same criteria as in Oakland’s proposal) is higher than that being proposed for Oakland—is an effective 3.12% on San Francisco payroll. The GRT marginal rates also have increases built in through 2023-24.

The City of Richmond’s Measure U was placed on the ballot by City Council in response to the need for increased revenues; voters approved the Measure November 2020 and it took effect January 1, 2022, too recently to have any measure of its impact. Measure U replaced an employee-based tax with a gross receipts tax based on sector and amount of revenue, similar to Oakland’s measure. Rates range from a flat $100 for businesses with less than $250,000 in gross receipts to marginal rates ranging from $0.60 to $6.80 per $1,000. Richmond’s sectors closely mirror those in Oakland’s current (and proposed) gross receipts tax; its highest tier is $50,000,000 and above in gross receipts. Richmond’s administrative headquarters tax goes up to $2.40 per $1,000 in annual payroll.

Funding public services helps the economy

Oakland’s continued economic competitiveness will depend on the city’s ability to provide quality services, in particular to address business concerns about safety, cleanliness, administrative services, infrastructure and homelessness. Labor Center research on California’s economy showed that the state’s progressive public policies supported the state’s robust economic growth, in contrast to states that pursued austerity policies.

The locally-based businesses with narrow profit margins in every city—the service economy, in particular small retail and restaurants—need two things: support for their lower-wage workforce to live close to work and remain in their neighborhoods and a core urban workforce to sustain their customer base. The progressive tax structure successfully allows the city to raise significantly more revenue to keep Oakland safe and welcoming and target investment in new and small businesses, without burdening the businesses who won’t be able to pay more.

Public spending plays an important role in both economic recovery and sustainable economic development. Comprehensive studies of economic impact suggest that investments in public services have a longer-term return to the economy and direct subsidies to businesses. Sustainable economic development requires a strategy of public investment, targeted business support that nurtures key economic clusters, and growing a local workforce with relevant skills. Economic development strategies focused on low-tax environments have not proven to be successful in creating quality jobs and sustaining economic growth.

How general fund revenues can help Oakland’s economy

The Blue Sky report estimates that the Bas-Fife proposal would raise between $35.4 and $41.0 million by full implementation in 2023-24 (the lower number generated by their elasticity scenario). This represents a significant increase in the revenues available for supporting Oakland’s economy. Under its current formulation, Oakland’s GRT is projected to raise about $100 million out of $650 million in general purpose fund (GPF) in FY22. The most recent actuals for FY2019-20 show $98,036,080 in business license tax, and projects $100,100,000 for FY23 as the economy continues to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic impacts. GPF revenues for FY2023 are projected to be $760,238,882, so the estimated increase in GRT revenues would be about a 4% increase in the general purpose fund.

This revenue increase will also help bring needed stability to Oakland’s overall revenue mix. Some of Oakland’s revenue sources grew significantly from FY20 to FY21—property tax revenue and real estate transfer taxes grew by 10.3% and 23.8%—reflecting the rapidly rising property values and real estate activity that have fueled similar increases across California (budget numbers from Oakland’s CAFRs). The impact of COVID-19 can be seen in the 45.8% drop in transient occupancy tax revenues; service charges and parking revenues also fell significantly. In FY20 Business license taxes was the largest general fund revenue category after property taxes; they have stayed relatively stable, growing 6.3%, helping stabilize Oakland’s overall revenue gain of 6.6%. High inflation over the past year, however, means that the city’s ability to maintain even existing services will not be possible without additional revenues.

Oakland has struggled with sufficient revenues: the city needs additional revenue to fund the services necessary to maintain the city’s position as an economic center in the Bay Area. Local government employment has lagged behind in the economic recovery, despite one-time spending: it is down 6.2% in California since 2020 and down 15% since 2007 when accounting for population growth. Economists have emphasized throughout the pandemic that investing in the local government workforce is critical for economic security. Local governments implemented significant spending cuts after the 2007-09 recession; by FY 2013 Oakland had cut more than $170 million and continued to face a nearly $60 million deficit. Local government spending in California has not regained pre-Great Recession levels when adjusted for inflation.

This decade-long stagnation in local government recovery has implications for the health of California’s economy. Public spending has a significant multiplier effect, as local government spending on staff and goods and services circulates in the local economy. The additional GRT revenue would contribute to closing this gap, supporting local investments and jobs. With additional general fund revenues, Oakland can grow its capacity to support new business creation, address challenges that businesses have identified as barriers, and help small businesses thrive.

Staffing shortages in key departments in the city add to the costs of doing business by shifting the cost of core public functions (safety, sidewalk repair, business district cleanliness) onto neighborhood businesses. The understaffing and under-resourcing of key agencies also adds uncertainty and delay to everyday business processes, such as permitting and licensing, which adds costs to businesses and may hinder expansion. According to data provided by the city, of the 4,704 FTE authorized positions in the city’s workforce, 584 or 12% were vacant in 2021. These are positions that the city needs to function smoothly, but for which there are not sufficient funds. 28% of the city’s departments were identified as being “chronically understaffed,” with vacancy rates over 10% for the past five years, and 44% were “critically understaffed” with a vacancy rate of over 18%. These staff shortages directly impact the ability of all businesses to get needed support, navigate licensing and other regulations, and for communities to be maintained at a level conducive to successful economic growth.

Conclusion

As businesses return to “normal,” Oakland will continue to compete on quality of life, its strong labor pool, urban amenities, and agglomeration economies. A progressive business tax equitably shifts responsibility to larger businesses to benefit Oakland’s long-term economic health and is in alignment with the approaches being taken by similar jurisdictions. Oakland’s small businesses in particular—which generate economic activity that stays local and supports Oakland’s residents of color—could benefit from both a reduced tax burden and city funding for additional services to improve the city’s business climate.

About the author

Sara Hinkley is a specialist in the Low-Wage Work program at the Labor Center. She has an extensive research background in labor, workforce, and economic development policy in California and nationally. She has worked for the California Labor Federation, Justice for Janitors, and Good Jobs First. Dr. Hinkley has provided research consultation for the Institute of Urban and Regional Development, the Goldman School of Public Policy, the Center for Community Innovation, the County of Los Angeles, and Inclusive Economics. Sara teaches courses in economic analysis and community and economic development in the Department of City and Regional Planning at UC Berkeley. She holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning from UC Berkeley.